Surveying Safely in the Outback

The second edition of the RICS Surveying safely guidance note, which became effective in February, contains valuable lessons for all surveyors (rics.org/surveyingsafely).

KPMG’s property due diligence team operates across Australia in all sectors and on all building types, and every time the risks are different. We could be inspecting a roof-level plant room in a 30-storey building, or travelling to an asset someone owns in the middle of nowhere.

Take for example a job I found myself doing: inspecting remote schools in the outback of Western Australia. The fact that the guidance note does not comment on certain aspects of working in this environment does not permit inadequate consideration of the risks. On the contrary, when there are such unknowns we use the tools and advice at our disposal to ensure as many of the risks are identified as possible, so we can manage or mitigate them. As property professionals, we are expected to have a level of competence sufficient to enable us to take personal responsibility for managing health and safety.

In order to begin the risk assessment at these schools, I chose to determine the itinerary first so I would have something I could sound out with a colleague. The isolated inspection schedule included 11 of the schools to be visited, with an estimated driving distance of 2,000km over nine days. Although some days would involve no driving, others would be nothing but.

Part of confirming the itinerary included contacting each school. This was more than just a case of confirming the time and date of my attendance; it was also an opportunity to gather as much information as possible. The buildings themselves weren’t considered special or unique, and the majority were transportables or those constructed as part of the Building the Education Revolution initiative for new cavity-walled classrooms. Apart from ensuring access to all structures, gathering details about local conditions was a priority. It included details you wouldn’t be able to find online – first-hand accounts of conditions, accommodation, phone signal and, in one instance, an Aboriginal funeral that would be taking place.

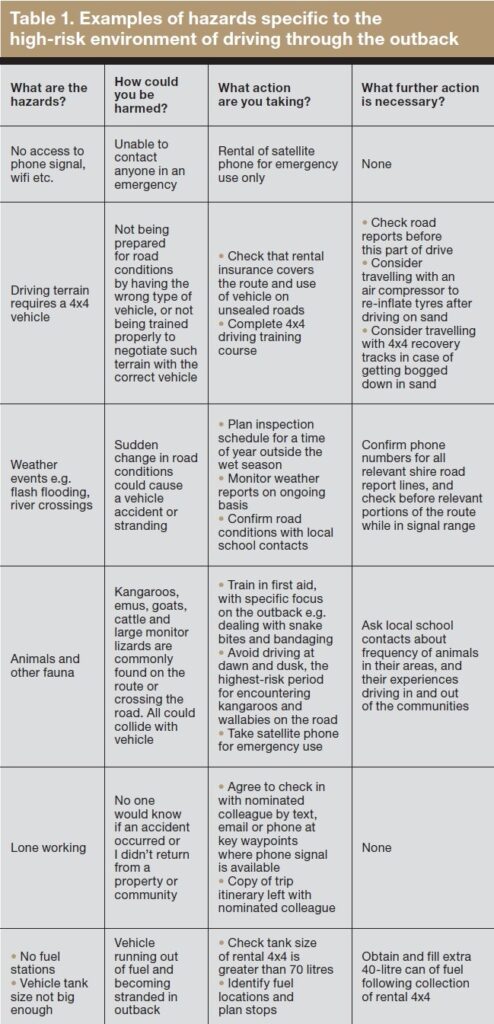

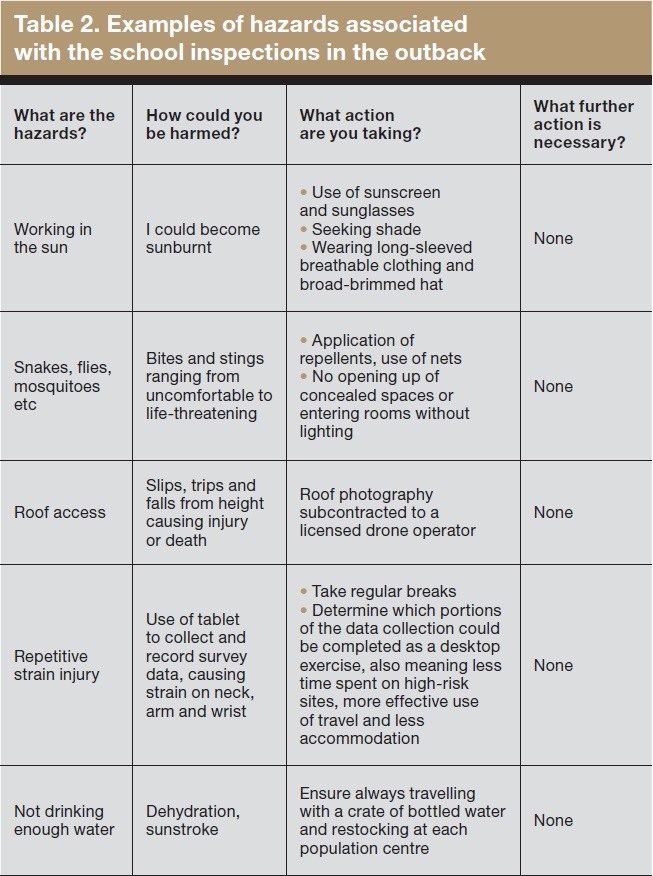

Once we had determined that the inspection schedule could not be fulfilled by flying to each location, a driving route was established and journey times estimated. With my itinerary to hand, a risk management exercise could be performed by considering how my plan of action might deviate from expectations. Table 1 provides information on hazards specific to the high-risk environment of driving through the outback, while hazards associated with the inspections themselves are detailed in Table 2.

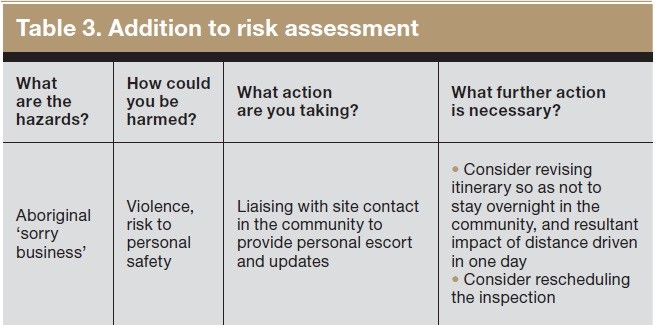

The Surveying safely guidance note mentions at the outset that, from an international perspective, it is important to consider cultural differences in terms of health and safety. Aboriginal communities, for instance, treat deaths and funerals with a high level of cultural sensitivity and respect.

In such cases, the risk level for outsiders varies with each community for several reasons, including the seniority of the community member who has passed away and whether or not alcohol is prohibited in the region.

Often a ceremony will not commence until most of the affected tribe members have travelled to the community, which can take days or weeks. In the interim, unrest and violence is known to break out in certain communities, creating an especially high-risk environment for outsiders; this period of mourning is known to Aboriginals as ‘sorry business’.

While I was confirming access arrangements to a remote Aboriginal community school, the principal advised me that the community was observing sorry business, and I therefore had to update my risk assessment (see Table 3).

So long as you take the time to go through your itinerary and your scope of work step by step, you should identify all the hazards. But take the time to review the document with a fresh set of eyes, or pass it to other colleagues who have experience relevant to the job.

Most of the risks being considered concern well-being or life safety; however, something I have not touched on that we must all consider frequently are the commercial risks associated with our day-to-day roles, which still apply in the context of working remotely.

These include reputational risk should something go wrong or be mismanaged, or financial risk if data for a remote site is lost and a fresh visit is required, which not only entails further costs but also subjects a person to all the previously identified hazards once more.

In today’s agile working environment, we are less often limited to one project at a time. For example, while he was working on the same school project elsewhere in Western Australia, a colleague found himself taking a conference call about the sale of an A$250m office asset that patched in a Sydney client and Canadian investors – all of this on a dirt track after an inspection at a remote community school.

This blurs further the definition of the workplace, and underscores the importance of assessing risk. It is assumed that the basic requirements of making our place of work comfortable – such as access to water and temperature control – are being met, but inside a vehicle this will not always be possible. We are each responsible for assessing our own environments.

Bear in mind that other areas of the world will have altogether different considerations. For example, working in Papua New Guinea it is necessary to take medication to prevent malaria infection, and appoint a security guard detail to escort oneself between sites in rural areas. Such considerations are also likely to entail increased fees for the client.

CJLM

This article first appeared in RICS Built Environment Journal, April-May 2019